The brook trout is among the most iconic species for anglers in eastern North America. This lovely fish registers as a powerful symbol because of its beauty, imagery in art and literature, and role as an indicator species of the overall health of an environment.

My use of the word “lovely” gives away the reason I hold this small fish in such high regard. There isn’t a more striking fish in the East, at least one that’s targeted on a fly. The sides of the brook trout are sprinkled with dots and dashes of red, orange, yellow, and the occasional blue. Its belly—especially in the autumn—turns bright orange, while its upper back is dark green or even black, providing stunning contrasts. The first time I held a brook trout, I thought that an artist had painted all the colors of a fall Appalachian forest on this one small, living palette.

Yet the camouflaged back of this fish makes it almost invisible in a stream. Not until we pull a brookie from the depths of its cool, dark pool can we see and truly appreciate these small masterpieces. Sometimes when I sit near a stream, I almost feel sorry for the hikers who quickly walk by, seemingly oblivious to the beauty of the creatures hiding among the cobbles on the stream’s floor. The hikers’ lack of attention in turn makes me think more deeply about what I might be missing in nature when I am distracted.

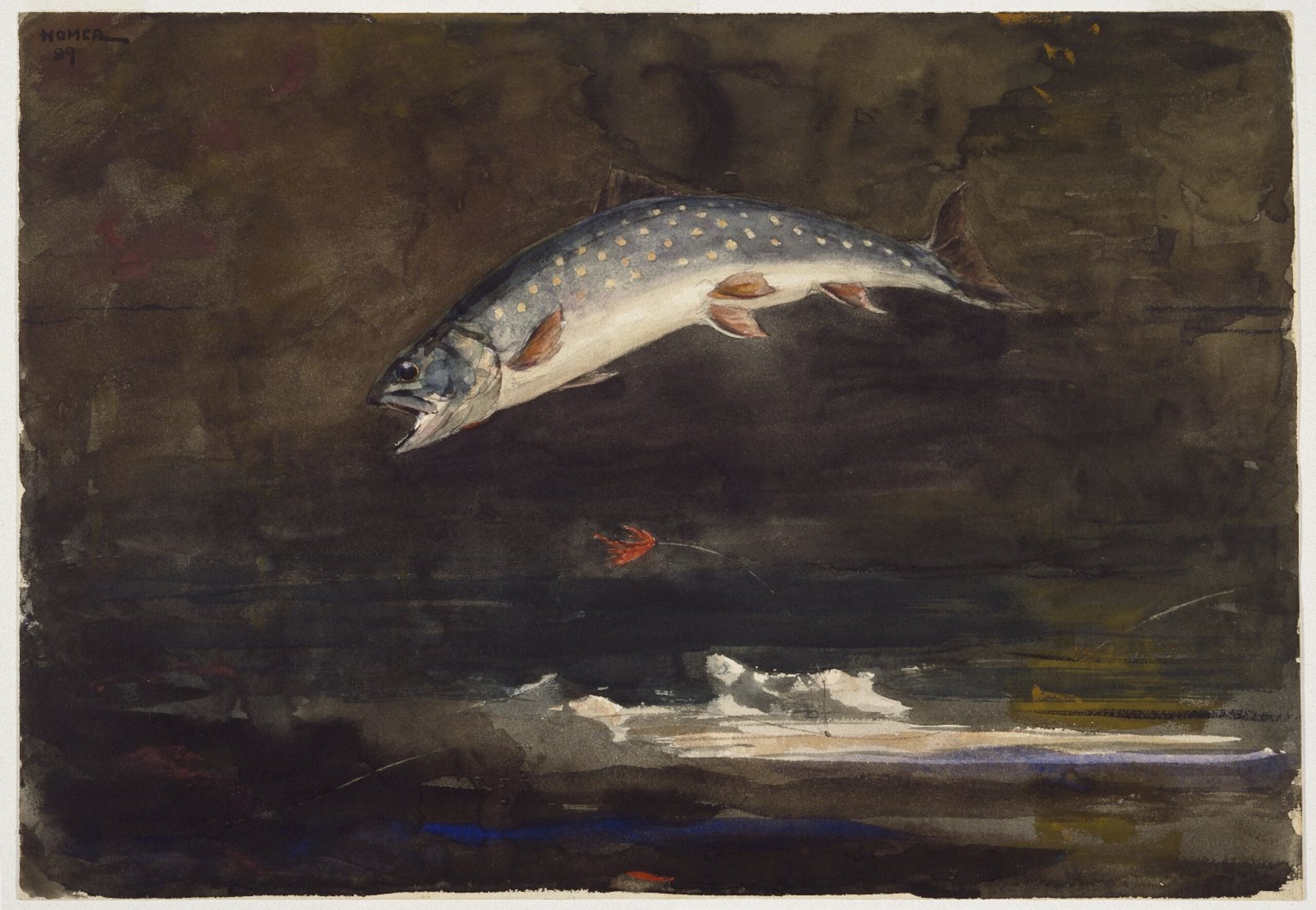

For centuries, the brook trout has inspired artists and writer alike. Its image has graced the canvases of America’s best sporting artists, beginning in the 19th century with Winslow Homer’s paintings of leaping brook trout. His celebrated watercolor of 1892, A Brook Trout, is one of the most recognizable images of fish in American art. It both depicts the species with accuracy and places the fish in an almost unimaginable aerial pose.

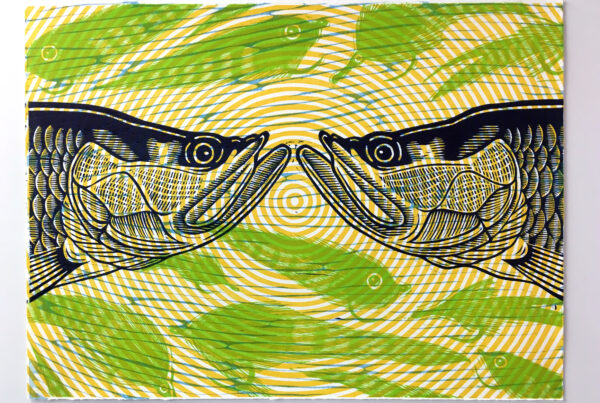

Homer’s focus on the brook trout should not be particularly surprising given that, during the 19th century, it was the only salmonid in many eastern rivers, a prominent setting for his art. The brook trout remains a popular subject today among piscatorial artists like James Prosek, whose vivid watercolors of small brook trout are set among the streams of his native Connecticut; Joseph Tomelleri, whose scientifically detailed work has appeared in more than a thousand publications and whose client list (ranging from Bass Pro to Zebco) makes him perhaps the best-known fish illustrator today; Bob White, whose fish and fishing watercolors always inspire me to start planning my next fishing trip; and Mary Beth Meeks, whose block prints portray a slightly different but equally beautiful rendition of the fish. These individuals are not only talented artists, but also avid anglers who effectively depict the essence of fish and their landscapes.

The allure of brook trout and the landscapes where they are found are also reflected in an abundance of literature. Contemporary authors such as James Babb, Chris Camuto, John Gierach, Nick Lyons, Craig Nova, and W. D. Wetherell have written in great detail about the intersection of life and angling for brook trout. Their work has led me to contemplate the role of the brook trout in my own life. Other works focus more on biology and natural history, with Nick Karas’s book Brook Trout serving as the standard-bearer for any and everything about brook trout. Before the mid-20th century, the connection between literature and brookies specifically is harder to trace, but trout in general and fly fishing in particular provided fertile waters for a rich body of work. The great naturalist John Burroughs (notably in his essay “Speckled Trout”) and the writers Theodore Gordon, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Maclean, and Henry David Thoreau all fished in brookie waters.

Beyond the creative inspiration provided by the brook trout is that its presence tells us a great deal about the health of the larger environment. The brook trout is an indicator species for streams, lakes, and watersheds. Because they are most plentiful in largely unspoiled conditions, their association with clean intact environments is another reason the brookie has developed a dedicated following among fly anglers. When I have a brook trout in my hand, I know the water in which I am standing is nearly pristine.

Writer Chris Camuto notes in A Fly Fisherman’s Blue Ridge, “Wild trout are a sign the land is doing well.” And according to Gary Berti, a former coordinator of the Trout Unlimited Eastern Brook Trout Campaign, “brook trout are the canary in the coal mine when it comes to water quality. . . Declining brook trout populations can provide an early warning that the health of an entire stream, lake, or river is at risk.”

The brook trout is also the most widespread species of trout, often described as the only native member of the Salmonidae family found in the eastern United States. This is technically incorrect, because the closely related Arctic char lives in a handful of isolated ponds in northern Maine, Atlantic salmon continue to swim in the waters of several rivers and lakes in Maine and many more in eastern Canada, and lake trout are also found in the deep lakes of New England. The brook trout, however, is the only native salmonid found south of New England, in highland areas such as the Allegheny and Blue Ridge Mountains.

The brook trout’s native range roughly spans the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, from northern Georgia to northern Labrador and west to the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay regions. Within this vast geography exists such distinct populations as “coaster” brook trout in the Great Lakes; “salter,” or sea-run, brook trout along the coast of New England; southern and northern strains in the Appalachian Mountains; and unique strains in some of Maine’s ponds.

Habitat scale or opportunities correspond with the scale or size of the fish. Even so, it’s strange that the small but mature six-inch brook trout I caught in foot-deep clear streams in South Carolina are the same species as the giant 20-incher I caught in the deep-black rivers in Labrador. Geography matters.

Because of stocking efforts during the 19th and 20th centuries, char and trout today are found outside their natural range and overlap with introduced species such as brown and rainbow trout. The brook trout is now widespread in western North America and has become an invasive pest, displacing many native cutthroat trout species. So while conservationists in the East work to protect brookies, those in the West seek to remove them. Their presence and its ramifications became clear to me while fishing in Montana’s Lee Metcalf Wilderness Area, far outside the brook trout’s natural range. For every native cutthroat we caught, I probably landed 10 brook trout. Although that experience remains special given the sheer number of fish I caught, the memory is somewhat tempered by the knowledge that brook trout don’t belong in Big Sky country. The experience would have been more pure had I caught only native cutthroats.

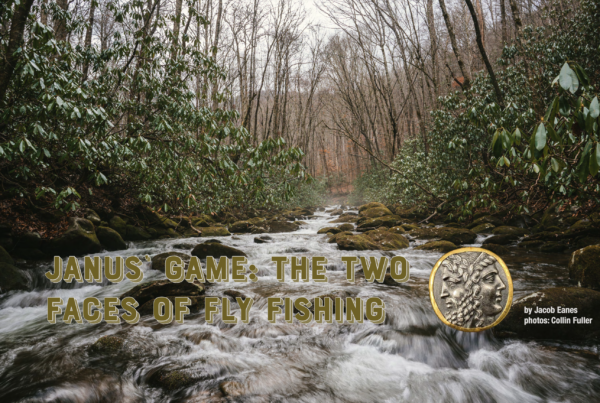

The environment in which the brook trout is found is also part of its past and present appeal. To fish for brook trout is often to fish in the last remote and rugged landscapes in the East, “fishscapes” not polluted by the stocking trucks that dump nonnative brown and rainbow trout in most of the East’s accessible cold waterways. Part of fishing’s allure in general is the landscape, whether the jungle-like mangrove swamps of the tropics or the cold, boulder-laden streams flowing from mountains. The brook trout’s home environment—streams in the old hemlock-covered Appalachian Mountains and silent ponds in northern New England—are some of the most beautiful landscapes in the eastern United States. One inviting feature of these waters is that they do not suffer the same levels of fishing pressure as lower-elevation streams that are more accessible. It’s common to spend a day completely alone while hiking up a brookie stream, even though you may be only a few hours from urban life along the east coast. During most trips to fish for brook trout, my only companions are brightly colored salamanders, birds in the treetops, and an occasional black bear. These streams are not home to large, blandly colored, hatchery-reared fish.

Anglers who hike up to cold trickles appreciate the intangibles that nature has to offer: great views from the tops of mountains, the physical challenge of getting to rugged streams, and the chance to catch colorful native fish. When brookies strike at the end of my invisible leader line, the mountain has bestowed upon me a living gift.

Today, brook trout in the eastern United States receive more conservation attention than they ever have, from growing numbers of local, state, and federal conservation and restoration projects. The simple yet understandable desire to catch big fish does not drive this interest. Brookies, in most of their range, are not and never will be big fish. I feel a sense of accomplishment when I catch an eight-inch fish in a headwater stream. The love of native fish and their landscapes is the motivation that largely drives the effort to improve and protect the brook trout’s habitat. To me, this is a healthier motivation than managing a species and ecosystem solely for producing trophies.

I am not naive about our past or current disruptions to landscapes of native trout. In almost all areas where brook trout are found, the axe and plow—if not the front-end loader—were close at hand at some point in the settlement of North America during the past three centuries, and nonnative trout have been stocked in every state. Pristine forested landscapes are rare in eastern North America today, including the South, except for a handful of old-growth forests scattered throughout the remote mountains. Nineteenth-century photos of the Green or Shenandoah Mountains show fields growing stumps and stone walls, not the mature forests we associate with these areas today. But wilderness can also be thought of in terms of personal meaning and experience and not just in relation to miles from roadways or thousand-year-old forests.

When I hike and fish a mountain stream, I sometimes like to imagine that its true headwater is in some remote wilderness well beyond my reach rather than my stopping point at the moment. Even if the true headwaters are within reach, I often stop fishing before I reach them so that the stream retains some secrecy in my mind. Wilderness is a place where native species still dominate, where one can find peace, meaning, and some mystery in the natural landscape. These places are the mountaintops, gorges, and remote ponds where colorful brook trout still hover in cool, dark waters. If wild and native brook trout are still out there, wilderness and clean pure water abide. As I look back with a present-day appreciation of how much that first experience of catching brook trout affected me, some lines from Moby-Dick come to mind: “Take almost any path you please, and ten to one it carries you down in a dale, and leaves you there by a pool in the stream. There is magic in it.” Indeed, I still find magic in those brookie pools and streams.